What Your Child Is Expected to Know in Year 3 Maths (Australia)

Introduction

Year 3 is often the first year where maths stops being purely mechanical and starts demanding real thinking. Up to Year 2, many children can cope by memorising steps or copying patterns. In Year 3, that safety net begins to disappear.

Teachers now expect students to explain their thinking, understand why an answer makes sense, and apply maths to everyday situations. This is why many parents are surprised when a child who “was doing fine before” suddenly becomes slower, less confident, or frustrated with maths.

Understanding what is expected in Year 3 helps parents spot gaps early, before they quietly grow into bigger problems in Years 4 and 5.

Number and Place Value

By the end of Year 3, Australian students are expected to be comfortable working with three-digit numbers, not just recognising them but truly understanding how they work.

This includes knowing the value of each digit in a number, comparing numbers correctly, and ordering numbers from smallest to largest (and vice versa). A child is expected to understand, for example, why 407 is larger than 389, not just guess based on the first digit.

Many difficulties at this stage come from shaky place-value understanding. Children may read numbers correctly but still struggle to compare them, misjudge which number is larger, or make frequent errors when regrouping during calculations. These issues often go unnoticed because answers may still look “close enough” in simpler questions.

Place value is not a small topic that gets left behind. It directly affects how well a child handles addition, subtraction, fractions, decimals, and even algebra later on. Weak foundations here tend to resurface repeatedly in later years, even if the child appears to cope for a while.

Addition and Subtraction

In Year 3, addition and subtraction go well beyond quick mental sums. Students are expected to work confidently with two- and three-digit numbers, often across multiple steps, and to apply these skills to word problems.

Children must be able to choose appropriate strategies: sometimes calculating mentally, sometimes using written methods. More importantly, they are expected to understand why those methods work. This is where many students begin to slow down.

A common difficulty at this stage is regrouping (often called “borrowing” or “carrying”). A child may know the steps but apply them mechanically, leading to frequent careless mistakes when numbers get larger or when problems are presented in words rather than symbols.

Word problems increase significantly in Year 3 and often involve extra information that must be filtered out. Students are expected to decide whether a problem requires addition or subtraction and to explain their reasoning. Many children can perform calculations correctly but struggle to interpret what the question is really asking.

When a child starts avoiding word problems, rushing through them, or becoming anxious during homework, it is often not the calculation itself that is the issue, but the thinking and language load that Year 3 maths now demands.

Multiplication and Division

In Year 3, multiplication and division are introduced as ideas, not just facts to memorise. While times tables become important, students are expected to understand what multiplication and division actually represent.

Children learn multiplication through equal groups and arrays and division through sharing and grouping. For example, students should be able to explain why 12 ÷ 3 equals 4 by showing how 12 objects can be shared equally into three groups, not just by recalling a fact.

Many children appear to “know their tables” but still struggle with division. This usually happens when multiplication has been learned as rote memory rather than as a concept. Without a strong understanding of grouping, division questions, especially word problems, quickly become confusing.

Year 3 also introduces the idea that multiplication and division are related. Students are expected to recognise that 4 × 6, 6 × 4, 24 ÷ 6, and 24 ÷ 4 are connected. This inverse thinking is new and can feel abstract for some children.

When multiplication is rushed or treated purely as memorisation, gaps form that often show up later in Year 4 and Year 5, particularly in fractions, ratios, and problem-solving. This is why a solid conceptual foundation in Year 3 matters far more than speed at this stage.

Number Patterns and Early Reasoning

Number patterns in Year 3 are not just about spotting what comes next. Students are expected to identify the rule behind a pattern and use that rule to predict missing numbers or extend the sequence.

Patterns may increase, decrease, or change in less obvious ways, such as alternating steps or using multiplication rather than addition. Children are often asked to explain how they know their answer is correct, which introduces early mathematical reasoning.

This is one of the first points where maths starts to feel less concrete. There may be no pictures to count and no obvious operation written down. Students must think logically and test whether their rule works consistently.

Many children struggle here because they try to guess instead of reasoning. Others find it difficult to put their thinking into words, even when they sense the correct pattern. These difficulties can be frustrating for children who are otherwise strong with calculations.

Although number patterns may seem like a small topic, they quietly prepare students for algebraic thinking in later years. Difficulty with patterns in Year 3 often reappears in Year 6 and Year 7 when variables and formulas are introduced.

Fractions (Early but Important)

Fractions are introduced in Year 3 in a simple-looking way, but this is where many long-term misunderstandings quietly begin.

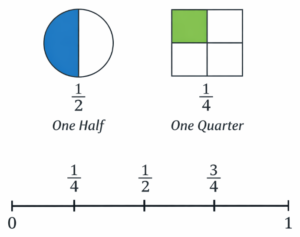

Students are expected to recognise and name common fractions such as one half, one quarter, and one eighth. They should understand that a fraction represents equal parts of a whole, not just a shaded picture. For example, a child should know that one quarter means one part out of four equal parts, whether the whole is a shape, a set of objects, or a number line.

Year 3 students also start comparing and ordering fractions with the same denominator and placing simple fractions on a number line. This requires them to think about size and proportion, not just labels.

Many children memorise fraction names without fully understanding them. This leads to confusion later when fractions stop being visual and start being used in calculations. A common issue is believing that a larger denominator means a larger fraction, simply because the number looks bigger.

Fractions introduced in Year 3 form the foundation for everything that follows in later years, including decimals, percentages, and ratios. When students struggle with fractions in Year 5 or Year 6, the root cause is often an incomplete understanding that began right here!

Data and Graphs

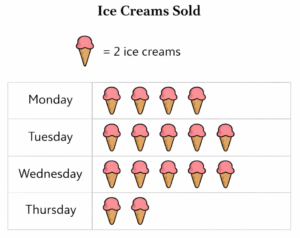

In Year 3, students are expected to do more than simply look at a graph and read off numbers. They must interpret information, compare values, and answer questions based on what the data shows.

Children work with tables, picture graphs, and simple bar graphs. They are expected to understand labels, scales, and headings, and to recognise what the data is actually representing. This requires careful reading and attention to detail.

Many mistakes at this stage are not mathematical errors but reading errors. A child may misread a label, confuse categories, or overlook what the graph is asking them to compare. Questions often involve language such as “most”, “least”, “how many more”, or “difference”, which adds another layer of difficulty.

Some students can draw graphs neatly but struggle when asked to explain what the data means. Others rush to answer without fully processing the information shown. These habits can lead to ongoing difficulties in problem-solving as data interpretation becomes more complex in later years.

Chance (Introduction to Probability)

In Year 3, students are introduced to chance in an informal and practical way. Rather than calculating probabilities, children learn to describe how likely an event is to happen.

Students use everyday language such as certain, likely, unlikely, and impossible to talk about outcomes. For example, they might decide whether it is more likely to rain tomorrow, or which colour is most likely to be chosen from a bag of objects.

Although this topic looks simple, it relies heavily on logical reasoning and clear explanation. Many children struggle to justify their answers, especially when two outcomes both seem possible.

Chance in Year 3 lays the groundwork for formal probability introduced in later years. When children are encouraged to explain their thinking rather than guess, they develop reasoning skills that support maths learning well beyond this topic.

Measurement

Measurement in Year 3 is strongly tied to real-life situations, and students are expected to apply maths in practical contexts rather than treat it as an abstract exercise.

Children work with time, length, mass, capacity, area, and volume. This includes reading analogue clocks to the hour and half-hour, comparing durations, and understanding everyday units such as metres, centimetres, kilograms, grams, litres, and millilitres.

One common challenge is that measurement questions often mix language and maths. For example, students may be asked to compare objects, estimate before measuring, or decide which unit is most appropriate for a given situation. These decisions are not always straightforward for children.

Area and volume are introduced informally, often using grids or units, which requires careful counting and attention to structure. Errors here are usually not due to poor arithmetic but due to missing a square, double-counting, or misunderstanding what is being measured.

Because measurement feels familiar from daily life, gaps in understanding are easy to overlook. However, confusion at this stage can later affect more advanced topics, such as perimeter, area formulas, and problem-solving involving real-world data.

Shapes and Geometry

In Year 3, geometry moves beyond simply naming shapes. Students are expected to describe and compare shapes based on their properties, using correct mathematical language.

Children work with common 2D shapes such as squares, rectangles, triangles, and circles, and are introduced more clearly to 3D shapes like cubes, rectangular prisms, cylinders, cones, and spheres. They are expected to recognise these shapes in real-life objects, not just in diagrams.

A key expectation at this stage is the ability to talk about features – for example, sides, corners (vertices), edges, and faces. Many children can identify a shape visually but struggle when asked to explain why it is a particular shape.

Classification is another area that causes difficulty. Students may be asked to sort shapes based on one or more properties, such as the number of sides or whether faces are flat or curved. This requires careful thinking and clear reasoning rather than memorisation.

When children find geometry confusing in later years, it is often because these early ideas were learned superficially. Geometry in Year 3 lays the groundwork for more complex concepts such as angles, transformations, and formal geometric reasoning introduced in later grades.

Space and Direction

Space and direction in Year 3 focus on helping students understand position, movement, and location in a structured way. This topic often looks simple but can be surprisingly challenging for many children.

Students work with maps, grids, and simple coordinates, and are expected to follow and describe routes using directional language such as left, right, north, south, forwards, and backwards. They may also be asked to give instructions or explain how to move from one point to another.

A common difficulty is keeping track of direction while visualising movement. Children may know individual directions but struggle to apply them consistently when several steps are involved. Confusion often increases when problems are presented in unfamiliar layouts or rotated diagrams.

Language plays a big role here. Words like “turn clockwise”, “next to”, “between”, or “opposite” require careful interpretation, and misunderstandings can easily lead to incorrect answers even when the child’s reasoning is otherwise sound.

Strong spatial understanding supports later learning in geometry, graphs, and even algebra. When space and direction are weak in Year 3, students may later struggle with coordinate geometry, transformations, and interpreting visual information across subjects.

Where Year 3 Students Commonly Struggle

Many Year 3 difficulties are not caused by a lack of ability, but by the increased thinking and language demands of the curriculum.

A common issue is understanding what a question is actually asking. As word problems become longer and more detailed, students may rush to calculate without fully processing the information given. This leads to correct methods being applied to the wrong problem.

Another frequent challenge is explaining reasoning. Year 3 students are increasingly expected to justify their answers using words, diagrams, or examples. Children who can find an answer but cannot explain how they arrived at it often lose confidence at this stage.

Transitions between ideas also cause problems. Moving from concrete materials to mental strategies, or from pictures to numbers, can be difficult for students who rely heavily on one method. This is especially noticeable in fractions, data interpretation, and number patterns.

Finally, small gaps in foundational skills — such as place value or grouping in multiplication — can quietly affect multiple topics. These gaps may not cause immediate failure but tend to resurface repeatedly as maths becomes more complex in later years.

How Parents Can Support at Home

Supporting a child in Year 3 maths does not require teaching advanced methods or adding extra pressure. Small, consistent habits make a far bigger difference than long practice sessions.

Encouraging children to talk through their thinking is one of the most effective strategies. Asking questions like “How do you know?” or “Can you explain that another way?” helps children organise their thoughts and build confidence.

Using everyday situations also helps maths feel meaningful. Cooking, shopping, telling the time, and reading simple graphs in newspapers or online all reinforce skills taught at school without feeling like extra work.

It is also important to focus on understanding rather than speed. Many children become anxious when they feel rushed, especially with mental maths. Accuracy and reasoning matter far more than how quickly an answer is produced at this stage.

When a child makes mistakes, treating them as part of learning rather than failure helps maintain motivation. Gentle correction and discussion are far more effective than repeated drills when misunderstandings are conceptual rather than procedural.

When Extra Support May Be Needed

Some struggle in Year 3 is normal, especially as maths becomes more demanding. However, ongoing difficulty can be a sign that a child needs additional support.

Parents may notice that homework regularly takes much longer than expected, or that a child becomes anxious or avoids maths altogether. Frequent careless mistakes, difficulty explaining answers, or a growing loss of confidence are also common warning signs.

Another indicator is inconsistency. A child may do well one day and struggle the next, especially with word problems or unfamiliar questions. This often suggests gaps in understanding rather than a lack of effort.

Seeking help early can prevent small issues from becoming entrenched habits. Support at this stage is not about pushing a child ahead, but about strengthening foundations so future learning feels manageable rather than overwhelming.

Next Steps for Parents

Year 3 is a pivotal year in a child’s maths journey. The skills introduced here quietly shape how confident and capable a student feels in later years.

Understanding what is expected allows parents to notice early signs of difficulty and respond before frustration sets in. Whether support comes from regular conversations at home, targeted practice, or extra guidance, the goal is the same: helping children build clarity and confidence in their thinking.

When foundations are secure, students are far better prepared to handle the increasing demands of maths in Years 4 and beyond.

Related Links